What is the molecular geometry of NO2–?

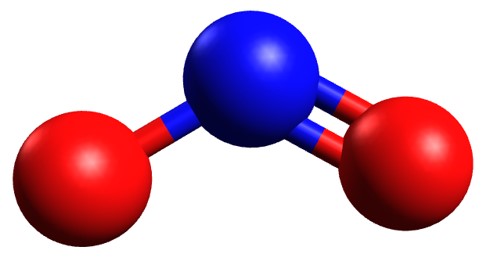

The molecular shape of NO2– is bent, or AX2E using Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory. Hence, the molecular geometry of NO2– only has 134 degree bond angles in the molecule. NO2– looks like this:

How do you find the molecular geometry of NO2–?

There is an easy three-step process for determining the geometry of molecules with one central atom.

Step 1: Determine the Lewis structure of the molecule.

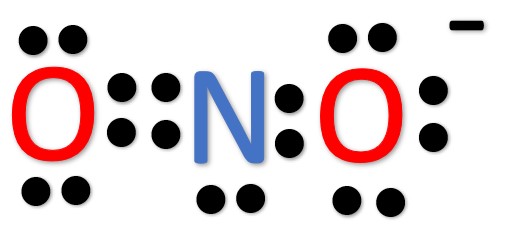

For NO2–, it is as shown below: For a full-explanation of how to figure out the Lewis structure, please go to Lewis Structure of NO2–.

Step 2: Apply the VSEPR notation to the molecule.

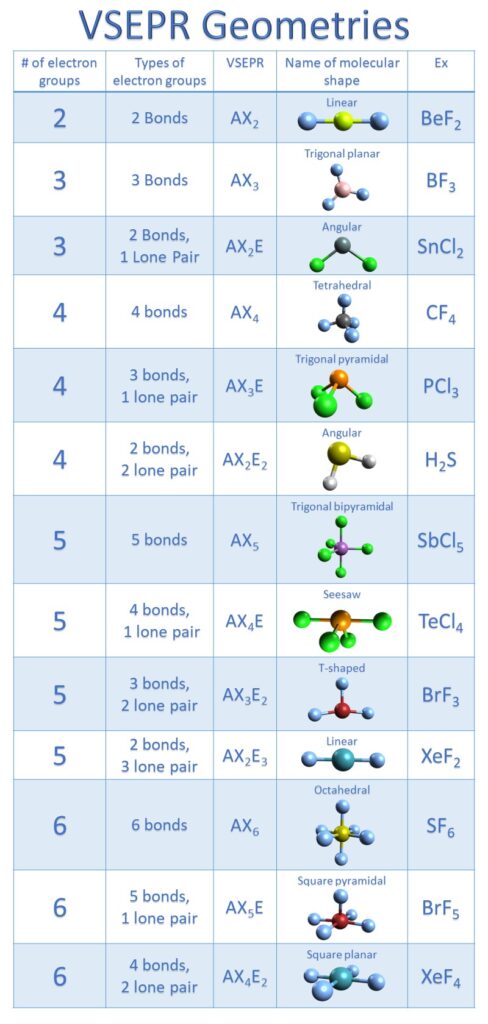

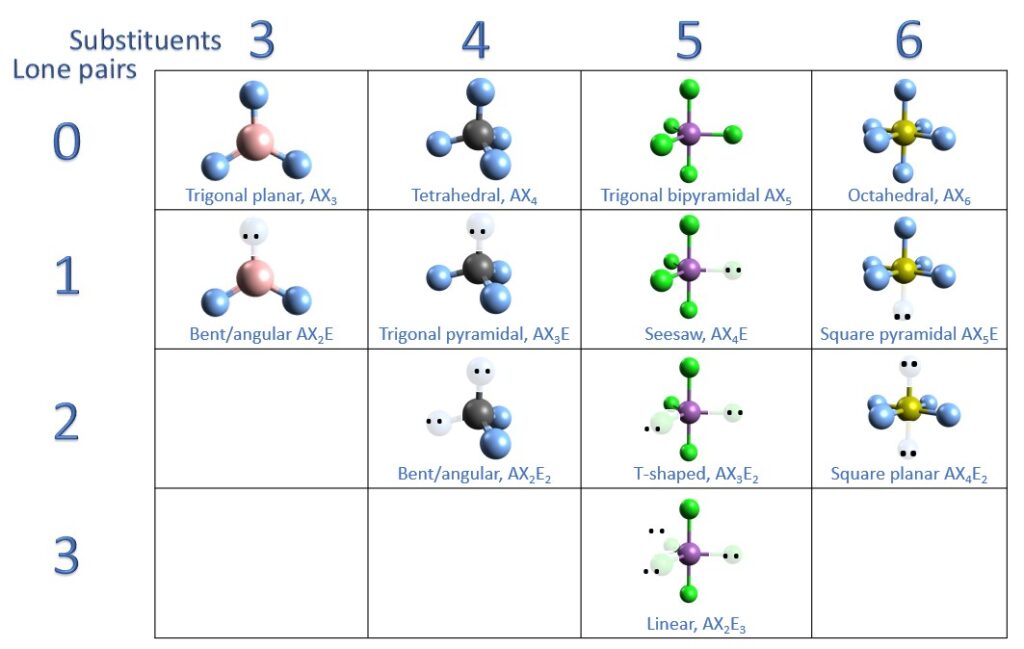

Apply VSEPR notation, A X E

A=Number of central atoms

X=Number of surrounding atoms

E= Number of lone pairs on central atom

For this one, we can see that it has one central atom, two surrounding atoms, and one lone pair of electrons around the central atom, making it AX2E. For the purposes of VSEPR, we are determining the geometry of the nitrogen atom, so we ignore the negative charge on the oxygen.

Step 3: Use the VSEPR table to determine the geometry of NO2–.

As you can see from the chart, AX2E molecule is bent.

Bond angles help show molecular geometry of NO2–

There is only one bond angle in this molecule. It is the O-N-O bond angle, which is 132 degrees. Even though one is a double bond and the other is a single bond, they are actually the same because of resonance, a process where the single and double bond are changing places so rapidly that they act like it is 1.5 bonds between the O and N.

Also, it is important to remember that there is a negative charge on the oxygen that has only one bond, giving the overall molecule a negative charge.

More about VSEPR and the molecular geometry of NO2–:

Let’s not forget, the whole purpose of VSEPR is to minimize interactions between the substituents (atoms and lone pairs) of a molecule. We also know that electrons repel each other. Hence, simple molecules (like the ones we are looking) at will tend to place substituent atoms as far from each other as possible. We know this because of the bond angles associated with each of the four types of shapes.

Here is one way to remember this chart: Think about each lone pair as just replacing an atom. In the chart above we have tried to show how this works by just blurring out an atom for a lone pair.

For the 3 and 4 substituent molecules (AX3 group and AX4 group, respectively) it is easy to do this because each one of the substituent atoms is the same. So for AX2E, it is simple to see that we get trigonal pyramidal as the answer because we can replace any of the atoms with a lone pair because they are all geometrically equivalent. Same for AX3E because all of the atoms are geometrically equivalent.

It get a little trickier when we get to the 5 and 6 substituent molecules (AX5 group and AX6 group, respectively). Here, there is a geometric difference between the atoms on the axis (called axial substituents) and the ones around the middle, called the equatorial substituents. Thus, we can’t just substitute a lone pair for any old atom. So…..what we need to remember is that for the AX5 group, you need to replace equatorial atoms with lone pairs AND for the AX6 group, you need to replace the atoms on the axis with lone pairs, as we have shown above.

Some video to make it a little simpler:

FAQs:

Q: Are these bond angles exact for each molecule?

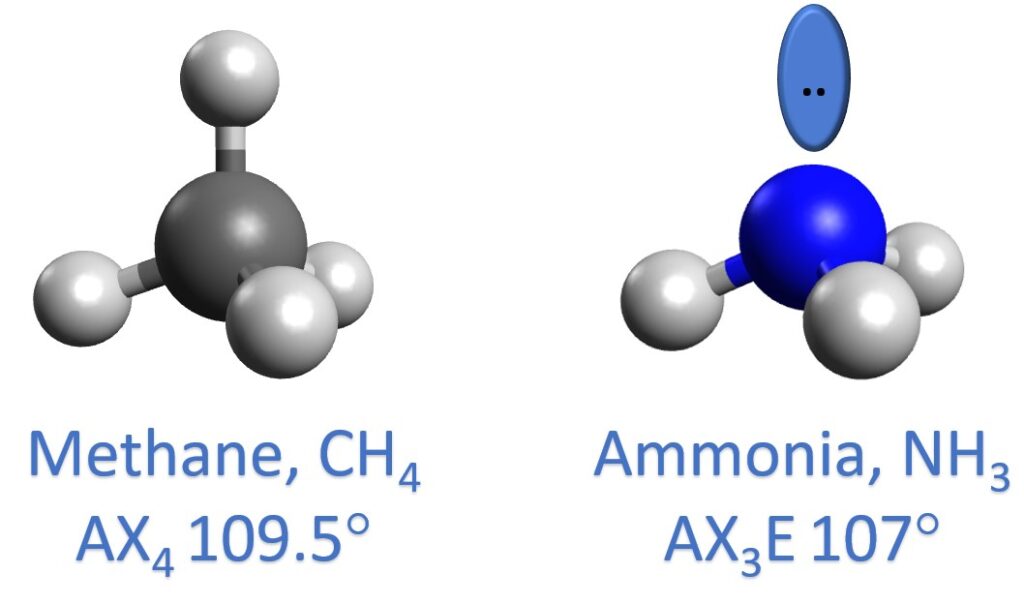

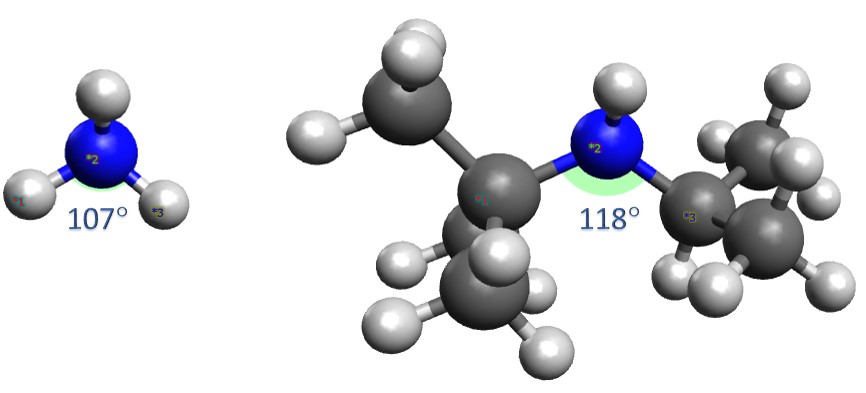

A: No, the bond angles are slightly influenced by whether the substituent is an atom or a lone pair and by atomic radii. Hence, the bond angles shown are close estimations, and not exact. A good example of this is methane and ammonia, as shown below. The lone pair in ammonia has a different repulsion effect than the hydrogen of methane, and therefore a slightly different bond angle.

Q: Does VSEPR theory work for more complex molecules?

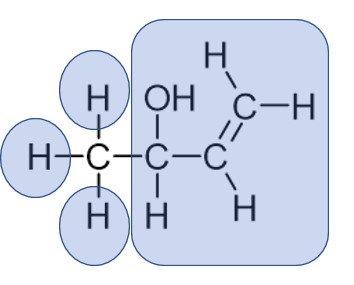

A: Yes, it can, however, it is important to remember that VSEPR is a tool and has its limits. One way you can use VSEPR is to call a group of atoms one substituent. Below is an example of this.

In the example above, we will only examine the carbon furthest to the left. VSEPR predicts this will be a tetrahedral carbon atom as it has the AX4 configuration of four bonded groups and no lone pairs, as we treat each hydrogen atom as a separate substituent and the everything else residing to the right of the carbon as one substituent.

We can do the same thing for the carbon second from the right, as shown in the image above. Each blue bubble represents a different substituent group (or atom) coming off of that carbon. As you can see, there are three blue bubbles of substituents and no lone pairs, meaning the VSEPR notation at this specific carbon is AX3, meaning it will be trigonal planar.

For more on this, please see our VSEPR guide at VSEPR molecular shape study guide

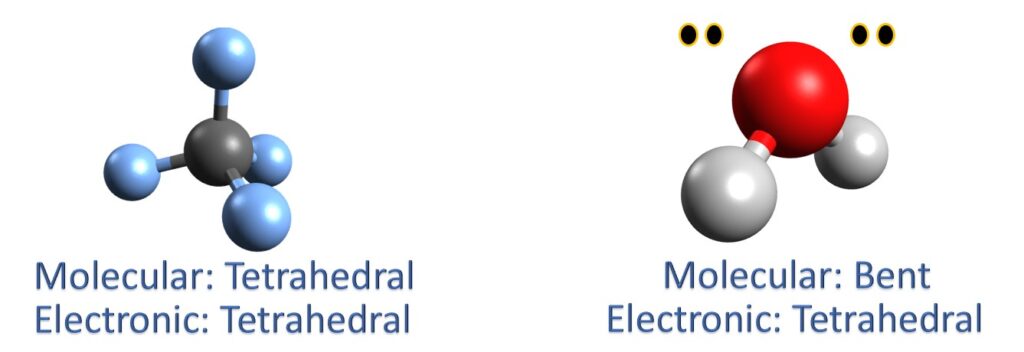

Q: What is the difference between the molecular geometry and the electronic geometry of a molecule?

A: The molecular geometry only takes atoms into account, whereas electronic geometry accounts for both atoms and lone pair electrons. This means that the electronic geometry and the molecular geometry can be different for the same molecule. Take for example CF4 and H2O. Both have tetrahedral electronic geometry, however H2O has a bent molecular geometry while CF4 has a tetrahedral molecular geometry (because the carbon of CF4 does not have any lone pairs).

Q: Does the steric group attached to the central molecule affect the bond angle?

A: Yes, it can. A good example of this is NH3 (ammonia) vs. tert-butyl isopropyl amine (TBIPA). While both of these molecules have a central nitrogen atom and are both AX3E molecules, they have different substituents coming off of the nitrogen. TBIPA is just ammonia with two of the hydrogens replaced by large hydrocarbons that want to be far apart from each other. Because of this, those large groups will move away from each other and have a larger bond angle than a similar molecule with just hydrogen atoms there. Therefore, even though both molecules are AX3E, they don’t have the same bond angles.

Q: What about double and triple bonds in VSEPR? Are they the same as a single bond?

A: For the purposes of VSEPR theory, yes they are. A double or triple bond will be treated the same as a single bond; it will be considered ONE substituent.

Lastly, here is the printable study guide!

This is our study guide. It is downloadable, printable and sharable. VSEPR molecular geometry study guide